Volvo launches all-electric bus

Chinese manufacturers have made the greatest progress in developing and introducing full size all-electric transit buses, capable of all-day operation.

In Europe, the major manufacturers have been slower to go down the all-electric route. The main manufacturers make their own diesel engines, often shared with much higher truck volumes, and understandably want to preserve their aftermarket business.

Some have been more active than others in developing hybrid vehicles. They are frequently seen as an important step towards the development of all-electric buses. Volvo has made the most progress, with more than 2,000 hybrid buses in service or on order. They are running in more than 20 countries.

Although Sweden is a large county with a comparatively low population, the nation has always been one of the most environmentally conscious in the world. Many city buses run on compressed natural gas (CNG) or biogas, while Volvo’s great rival, Scania, has strongly promoted ethanol as an alternative fuel. All have very clean emissions, although there is now little advantage over the latest Euro VI diesel engines.

While Volvo has built some gas-fueled buses, the message from many of its export markets was a preference for a hybrid solution, using smaller and cleaner diesel engines.

Toward the end of 2006, Volvo launched the 7700 Hybrid city bus, built in its factory in Wroclaw, Poland. The full low-floor layout had a 5-liter four-cylinder diesel engine mounted vertically and offset in line, driving through an Integrated Starter Alternator Motor (ISAM) between the engine and an automated manual gearbox, creating a parallel hybrid-drive system.

A major manufacturer like Volvo takes time to ensure that new technology works reliably and efficiently before releasing vehicles to customers. Much of the following two years was spent in development. Near the end of 2008, the 7700 Hybrid bus became available for volume production.

The entire hybrid driveline fit within the same space as a standard diesel-powered version of the same vehicle, minimizing the number of new parts created. Savings in fuel consumption were around 30 percent. At European prices for diesel, Volvo reckoned that the pay-back period for the higher initial price of the hybrid bus could be recovered within five to seven years.

In addition to the hybrid developments in Europe and North America, Volvo has a half share in Sunwin Bus, based in Shanghai. In the spring of 2009, Sunwin launched a hybrid bus and a full size all-electric bus. The latter was built to 40 feet, with banks of lithium-iron phosphate batteries at the rear. Sunwin reckoned that it had a range of 100 miles on normal city service.

By that time, Volvo was gaining experience with hybrid buses in Europe. Single-decker models were built complete in Wroclaw and the first examples entered service in Gothenburg. Double-decker chassis with the same driveline were bodied by WrightBus in Northern Ireland and entered service in London. Average savings in fuel consumption, compared with a standard diesel bus, were around 30 percent. After careful monitoring of these vehicles, Volvo approved regular production from the spring of 2010.

As production of hybrid buses ramped up in Poland, Volvo carried out many demonstrations as far afield as Brazil and Mexico. Normally, the higher initial price of a hybrid vehicle, compared to a standard diesel bus, had to be subsidised by public authorities. An increasing number were willing to pay that price in return for lower noise and emissions in urban centers.

Transport for London (TfL) is responsible for the entire public transport network in the Greater London area. TfL does not own any buses, but its routes are served by a number of bus companies, usually on five to seven year contracts. TfL specifies the numbers and types of buses to be used on each route and encouraged the introduction of hybrid buses on many of the busiest routes working through the city center. Volvo and WrightBus received regular orders from 2010 onwards, with more than 300 now serving the capital.

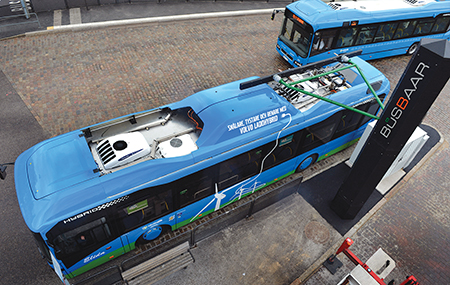

In the summer of 2011, Volvo announced plans to develop a plug-in hybrid bus that could drive longer distances solely in electric mode. The European Union gave a grant toward a project involving three buses in Gothenburg. At each end of the route, the buses took a fast – five to ten minutes – charge from an electrical station. The small diesel engine was retained and helped to charge the batteries while running in the suburbs. The buses ran solely on electricity in the city center and in particularly sensitive areas. The plug-in hybrid bus was able to reduce fuel consumption and CO2 emissions by around 70 percent.

Before that, Volvo had participated in the European Bus System of the Future project and had unveiled a novel articulated bus. The prototype had a full-length low floor but the front axle was moved further forward, providing a large area of low floor. The driver sat in a separate compartment, over the front axle, with a centrally-mounted seat. Although this bus remained unique, the central driving position would appear again.

Volvo continued to refine its hybrid vehicles. By the summer of 2012, more than 650 hybrid buses were in service or on order with customers in 18 countries. That number excluded around 200 hybrid buses that had been sold by NovaBus in North America. The first articulated hybrid model was added to the range in the summer of 2013.

With the introduction of Euro VI emission standards, Volvo made a particularly bold decision. It decided that, on the European market, it would offer full low-floor city buses only with hybrid drivelines. While the company had sold more hybrid buses than any of its competitors, they all continued to offer low-floor city buses with standard Euro VI diesel engines. Volvo continued to offer diesel engines in low-entry models and in double-decker chassis for the British and Irish markets.

The plug-in hybrid project in Gothenburg proved popular and successful. The vehicles used 81 percent less fuel than the equivalent diesel bus. Taking the overall energy consumption, including diesel and electricity, the plug-in hybrid gave an energy saving of 61 percent. The plug-in hybrid therefore became a regular option with the first vehicles entering service in Hamburg, Germany, before the end of 2014.

The latest development has been the introduction of an all-electric city bus. Three vehicles have just entered service in Gothenburg. They were built to an overall length of just less than 35 feet with the front axle beneath the driving compartment. That arrangement removed a pair of wheelboxes from the passenger area. The main doors were between the axles, giving rapid and easy passenger access.

Bearing in mind that all new designs have to be thoroughly tested and proved before handing over to customers, it is quite remarkable that Volvo has gone from hybrid to all-electric in a relatively short span of time.

Doug Jack is with Transport Resources in the United Kingdom.