Parsons Brinkerhoff’s Cliff Henke speaks to the aspects of successful Bus Rapid Transit planning

By David Hubbard

For over a century, Parsons Brinkerhoff, New York, NY, has viewed public transit as an inherent community-building tool that influences investment decisions and fosters economic development and revitalization. The firm helps transportation agencies plan, design and manage the construction of all forms of mass transit, which more recently includes its work in Bus Rapid Transit.

Cliff Henke, senior principal technical specialist for Parsons Brinkerhoff, spoke with BUSRide on his experience and view of BRT in America, particularly the aspects of projects in the early planning and funding phases.

What is your view of public transit and the growing interest in Bus Rapid Transit?

This country’s great dependency on the automobile has taken nearly a century to evolve. It will take many more decades to shape our view of public transportation much differently, but for now we are seeing a lot of exciting innovation. The downside is that transit, like government programs in general, is facing funding challenges as the demand for services is increasing.

In light of that, citizens in cities throughout the country are voting to tax themselves to raise additional funds to advance transit project spending. In this economic climate, cities are coming to realize that Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) is a flexible and less expensive solution, and more cities could use a BRT system in densely populated corridors. Rail is growing rapidly, but BRT is becoming a very attractive option because of advancements in equipment and technology over the last 10 years.

Is the public waking up to BRT?

The ultimate success of BRT is a matter of education and familiarity. It follows the evolution of conventional transit. In the 1960s, everyone was looking at heavy rail solutions. When light rail came along, the industry again set out to educate the public. Now everyone is learning more about the benefits of BRT.

Why are more cities considering BRT?

It comes down to what a municipality can afford in order to handle its transit capacity now and in the future. Bus Rapid Transit is proving itself as a cost effective solution, especially because of the shorter time it takes to implement BRT and make it operational. The advantage of BRT is its flexibility to connect with other transportation modes, and its ability to adapt to shifts in community development and changing policy.

Where does the process to design, construct and implement a BRT project begin?

The critical first step is to determine the needs for such a system. As a newer mode, the idea is to be absolutely clear on what the transit agency is trying to do, and why a BRT solution is even under consideration. The Federal Transit Administration (FTA) also looks first at purpose and needs when a transit authority submits its proposal for funding.

Who pulls the trigger?

The decision to move on the project typically comes from the local level and begins with a feasibility study or alternatives analysis. It culminates in a locally preferred alternative that will then be entered into the agency’s transportation improvement plan. Finally, the plan is submitted to the regional metropolitan planning body to be included in the region’s long range transportation plan.

What are the greatest challenges in the beginning of a project?

Gaining the show of support at the local level, politically and financially, greatly increases the chances of securing the requested funding.

How do politics help or hinder the planning process?

Politics are fundamental, and politics are what BRT planning is really all about. Political support is critical in moving a project forward. The decision to implement any mode of transportation requires a collective decision from the community, business leaders and government officials.

With the enactment of MAP-21, the FTA is more insistent on the level of commitment a community is willing to make toward funding.

Where does this commitment come from?

It takes political champions who can drive the request for funding. Private sector stakeholders, interest groups and businesses that have a stake in the development of the project also play very important roles.

What are the essentials in the BRT planning phase?

Planning is primarily a function of “getting all the ducks in a row” to ask for funding, which involves the feasibility and alternatives analyses. Akin to playing “devil’s advocate,” these studies essentially compare all viable transportation modes to the proposed BRT system and route corridors — light rail, streetcar or conventional transit — as well as compared to doing nothing.

The alternatives analysis narrows the choices based on the costs to plan, design and construct the system, as well as the ongoing operational costs.

After weighing in on all the possible solutions, the transit board will make its recommendation for the regional transportation investment fund.

Can you cite an example of your work in the planning phase?

We did an implementation study for Valley Metro, Phoenix, AZ, that included a number of BRT corridors, which the voters approved in the last transportation ballot initiatives. The board members envisioned the corridors going into effect so fast that they hired Parsons Brinkerhoff to look at the implementation stages and strategies for multiple corridors, prioritize their construction and get the stakeholders involved.

Then the recession hit and the funding dried up. The impact from recession was an especially hard hit for Phoenix. Though the city is gaining a foothold, Valley Metro had to temporarily shelve a number of projects due to its loss of funding — forces well beyond the control of the stakeholders. Nonetheless, such circumstances still affect the FTA’s view of a project.

Does every city get it right? What constitutes best practices and what would prove to be ineffective planning?

Typically, transportation bodies have not embraced BRT proposals right away. They have taken a wait-and-see approach to see how it plays out in other communities. Effective BRT planning requires the vision to look decades ahead with a clear plan for continual development.

Several scenarios could constitute what might be poor planning. The worst case would be not getting down to the real purpose of the proposed project, and not getting the needs right at the onset.

Projects also often sink when local politicians change their minds and reverse their position, or get voted out of office. We have encountered instances where a community had the funding lined up only to see it pulled when the leaders no longer wanted to follow through on the project for a variety of reasons.

Would you say successful BRT planning faces some long odds?

Conditions can change as the project evolves. The fiscal landscape can face devastating fluctuations, which the stakeholders adapt to or risk losing the community consensus. It is difficult not only to have those champions but also to sustain support over the length of any public transportation project. That’s why another major attraction of BRT is its quick implementation. It’s often as quick as a politician’s single term.

Who, in your mind, has done it right?

The Wasatch Front in Utah is a region that gets it. A consortium of the business community, religious leaders and political figures came together and were able to settle on what they truly wanted their regional transportation to look like in 50 years. Their takeaway was that they needed to invest seriously and heavily in public transit. They laid the groundwork for a series of successful ballot initiatives over the next several years that put the plans in place. This very conservative region has passed record levels of public transportation investment over the years. The FTA now looks to Utah Transit Authority as a model for what to do right.

How does a city determine the most opportune placement of BRT routes and corridors?

Typically, BRT corridors build from the most heavily traveled transit routes. A proposed BRT route also reflects the level of development a city intends for its transit corridors.

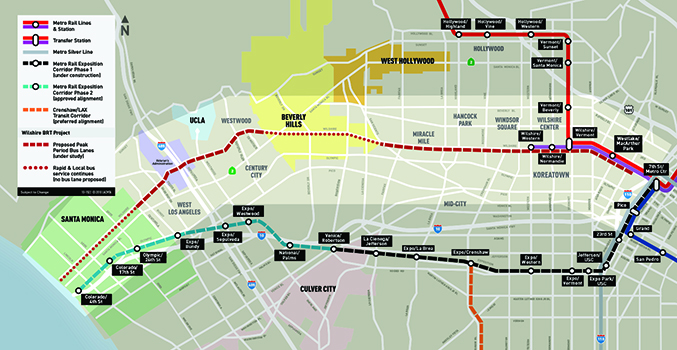

For example, one of Los Angeles’ first two BRT corridors is on Wilshire Boulevard, which the city is now upgrading with bus-only lanes and other improvements. Not only is this the most traveled bus route, the Westside Purple and Red Line subway lines also partly travel the same route beneath the roadway.

In Phoenix, the voters stated they wanted to service outlying areas, where there was only nominal service or none at all. As a result, Valley Metro has an express service in place that could eventually connect with a BRT system.

At what point do BRT planners engage engineers and architects in the project?

Planners engage these professionals early on, especially during the alternatives analysis, where they help conceptualize the corridors, stations and any suggested transit development.

Planners also need to present visualizations, which are renderings of the project, when they engage in public meetings.